A tale about data corruption, stack and red zone

January 27, 2014

It was a nice and calm work day when suddenly a wild colleague appeared in front of my desk and asked:

– Hey, uhmm, could you help me with some strange thing?

– Yeah, sure, what’s matter?

– I have data corruption and it’s happening in a really crazy manner.

If you don’t know, data/memory corruption is the single most nasty and awful bug that can happen in your program. Especially, when you are a storage developer.

So here was the case. We have RAID calculation algorithm. Nothing fancy – just a bunch of functions that gets a pointer to buffer, do some math over that buffer and then return it. Initially, calculation algorithm was written in userspace for simpler debugging, correctness proof and profiling and then ported to kernel space. And that’s where the problem started.

Firstly, when building from kbuild, gcc was just crashing1 eating all the memory available. But I was not surprised at all considering files size – a dozen files each about 10 megabytes. Yes, 10 MB. Though that was not surprising for me, too. That sources were generated from the assembly and were actually a bunch of intrinsics. Anyway, it would be much better if gcc would not just crash.

So we’ve just written separate Makefile to build object files that will later be linked in the kernel module.

Secondly, data was not corrupted every time. When you were reading 1 GB from disks it was fine. And when you were reading 2 GB sometimes it was ok and sometimes not.

Thorough source code reading had led to nothing. We saw that memory buffer was corrupted exactly in calculation functions. But that functions were pure math: just a calculation with no side effects – it didn’t call any library functions, it didn’t change anything except passed buffer and local variables. And that changes to buffer were correct, while corruption was a real – calc functions just cannot generate such data.

And then we saw a pure magic. If we added to calc function single

printk("");

then data was not corrupted at all. I thought such things were subject of

DailyWTF stories or developers jokes. We checked everything several times on

different hosts – data was correct. Well, there was nothing left for us except

disassembling object files to determine what was so special about printk.

So we did a diff between 2 object files with and without printk.

--- Calculation.s 2014-01-27 15:52:11.581387291 +0300

+++ Calculation_printk.s 2014-01-27 15:51:50.109512524 +0300

@@ -1,10 +1,15 @@

.file "Calculation.c"

+ .section .rodata.str1.1,"aMS",@progbits,1

+.LC0:

+ .string ""

.text

.p2align 4,,15

.globl Calculation_5d

.type Calculation_5d, @function

Calculation_5d:

.LFB20:

+ subq $24, %rsp

+.LCFI0:

movq (%rdi), %rax

movslq %ecx, %rcx

movdqa (%rax,%rcx), %xmm4

@@ -46,7 +51,7 @@

pxor %xmm2, %xmm6

movdqa 96(%rax,%rcx), %xmm2

pxor %xmm5, %xmm1

- movdqa %xmm14, -24(%rsp)

+ movdqa %xmm14, (%rsp)

pxor %xmm15, %xmm2

pxor %xmm5, %xmm0

movdqa 112(%rax,%rcx), %xmm14

@@ -108,11 +113,16 @@

movq 24(%rdi), %rax

movdqa %xmm6, 80(%rax,%rcx)

movq 24(%rdi), %rax

- movdqa -24(%rsp), %xmm0

+ movdqa (%rsp), %xmm0

movdqa %xmm0, 96(%rax,%rcx)

movq 24(%rdi), %rax

+ movl $.LC0, %edi

movdqa %xmm14, 112(%rax,%rcx)

+ xorl %eax, %eax

+ call printk

movl $128, %eax

+ addq $24, %rsp

+.LCFI1:

ret

.LFE20:

.size Calculation_5d, .-Calculation_5d

@@ -143,6 +153,14 @@

.long .LFB20

.long .LFE20-.LFB20

.uleb128 0x0

+ .byte 0x4

+ .long .LCFI0-.LFB20

+ .byte 0xe

+ .uleb128 0x20

+ .byte 0x4

+ .long .LCFI1-.LCFI0

+ .byte 0xe

+ .uleb128 0x8

.align 8

.LEFDE1:

.ident "GCC: (GNU) 4.4.5 20110214 (Red Hat 4.4.5-6)"

Ok, looks like nothing changed much. String declaration in .rodata section,

call to printk in the end. But what looked really strange to me is changes in

%rsp manipulations. Seems like there were doing the same, but in the printk

version they shifted in 24 bytes because in the start it does subq $24, %rsp.

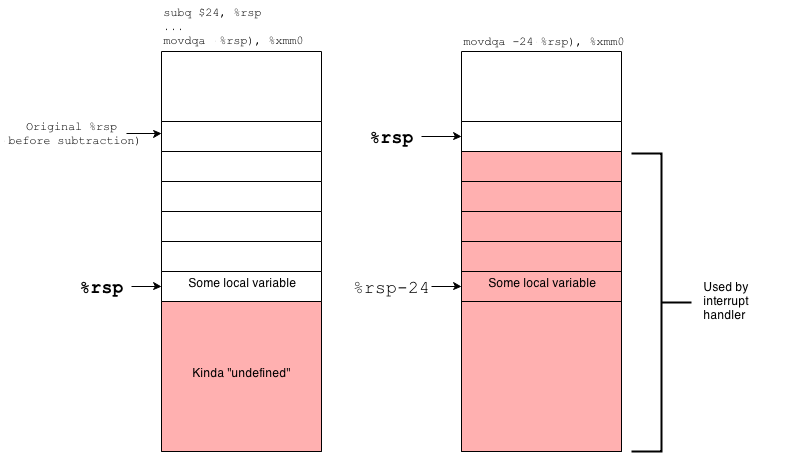

We didn’t care much about it at first. On x86 architecture stack grows down,

i.e. to smaller addresses. So to access local variables (these are on the stack) you

create new stack frame by saving current %rsp in %rbp and shifting %rsp

thus allocating space on the stack. This is called function prologue and it was

absent in our assembly function without printk.

You need this stack manipulation later to access your local vars by subtracting from

%rbp. But we were subtracting from %rsp, isn’t it strange?

Wait a minute… I decided to draw stack frame and got it!

Holy shucks! We are processing undefined memory. All instructions like this

movdqa -24(%rsp), %xmm0

moving aligned data from xmm0 to address rsp-24 is actually the access over

the top of the stack!

WHY?

I was really shocked. So shocked that I even asked on stackoverflow. And the answer was

In short, the red zone is a memory piece of size 128 bytes over stack top, that according to amd64 ABI should not be accessed by any interrupt or signal handlers. And it was a rock-solid truth, but for userspace. When you are in kernel space leave the hope for extra memory – the stack is worth its weight in gold here. And you got a whole lot of interrupt handling here.

When an interruption occurs, the interrupt handler uses stack frame of the current kernel thread, but to avoid thread data corruption it holds it’s own data over stack top. And when our own code was compiled with red zone support the thread data were located over stack top as much as interrupt handlers data.

That’s why kernel compilation is done with -mno-red-zone gcc flag. It’s set

implicitly by kbuild2.

But remember that we were not able to build with kbuild because it was

crashing every time due to huge files.

Anyway, we just added in our Makefile EXTRA_CFLAGS += -mno-red-zone and it’s

working now. But still, I have a question why adding Recently, in 2020 a kind person reached out to me and said that

the reason why adding printk("") leads to

preventing using red zone and space allocation for local variables with subq $24, %rsp?printk("") prevented the crash was simply because it

makes the calc function non-leaf - we call another function that can’t be

inlined. Kudos to Chris Pearson for sharing this with me after 6 years!

So, that day I learned a really tricky optimization that at the cost of potential memory corruption could save you a couple of instructions for every leaf function.

That’s all, folks!